On November 28, 2025, Yenching Academy welcomed Bruno Angelet, Ambassador of Belgium to China. The event opened with welcoming remarks by Dean Dong Qiang, who emphasized the significance of the ambassador's visit and noted that Belgium has been invited to Yenching Academy twice in recent years. Dean Dong highlighted the ambassador’s distinguished career in Asia, which began in Vietnam,where he became fluent in Vietnamese, and continues with his current role as ambassador to China.

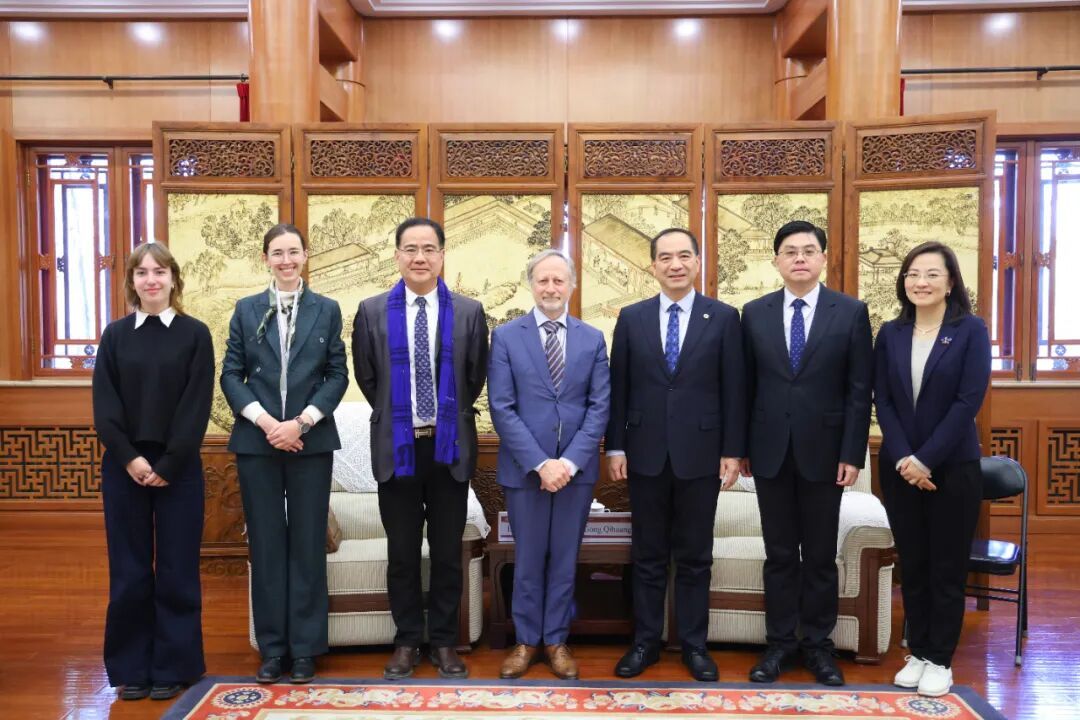

Prior to the lecture, the ambassador engaged in an engaging discussion with Peking University President, Gong Qihuang, exploring strategies to enhance Europe-China educational collaborations and deepen ties with the European Union, particularly in today’s complex global context. Dean Dong concluded his remarks by inviting Ambassador Bruno to begin his lecture, titled “Europe’s Long March: The History of European Integration.”

Ambassador Bruno opened by reflecting on the origins of European integration, emphasising the historical challenge of uniting multiple countries with diverse languages, cultures, and political systems. He highlighted how understanding history provides crucial insights into the collaborative processes that shaped Europe’s political, cultural, and economic landscape, offering the scholars a detailed perspective on Europe’s journey toward unity in light of its historical division.

In his lecture, Bruno Angelet began with discussing the historical formation of Europe, tracing its origins from antiquity to the cultural and political frameworks that shape the continent today. He began by explaining that the earliest conception of “Europe” emerged from ancient Greece. The Greeks not only gave Europe its name, possibly derived from Greek roots meaning “where the sun goes down”, but also introduced the first political distinction between Europe and Asia. Greek thinkers described Europe as the land of the free state, embodied in independent city-states, in contrast to the monarchic rule. He then turned to Rome, crediting the Roman Empire with providing Europe its political and institutional unity. Through Roman law, granting equality to free citizens across vast territories, Europe inherited a stable, cohesive legal tradition. Even after the fall of Rome, this law continued through the Catholic Church. Canon law preserved and adapted Roman legal principles, allowing them to shape medieval and early modern institutions. The ambassador highlighted Charlemagne’s coronation as a pivotal moment in the reconstruction of European unity. By reviving the imperial title, Charlemagne established a model of cooperation between Church and State that influenced European politics for centuries. The ambassador emphasised that Europe’s cultural unity emerged gradually. Despite linguistic and political differences, early Europeans shared common practices through Christianity: liturgical calendars, marriage customs, festivals, and community life centred on parish churches. He noted that artistic and architectural styles such as Romanesque, Gothic, and Baroque spread across borders. Everyday habits, from table manners to fashions, contributed to a shared way of life. The ambassador further emphasised in addition how intellectual thought spread through the “Republic of Letters,” a transnational network of scholars who corresponded in Latin added to the shared thought. This intellectual community fostered the circulation of knowledge beyond political boundaries and shaped Europe’s scientific and cultural development. Through their correspondence within these letters, Greek ideas, Roman institutions, and elements of shared medieval culture added another foundations of a European identity rooted in collective intellectual exchange.

The ambassador further explained how religion, politics, and culture shaped the continent. He began by examining religious and political divides, noting that the development of printing technology in the 15th century accelerated the circulation of reformist ideas. Holbein desired moderate reform within the Catholic Church, whereas Martin Luther advocated for change, translating the Bible into German to democratise Christianity and challenge the collusion between church and the State. These tensions led to widespread Protestant movements and triggered violent religious wars across Europe, culminating in the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. This treaty established the separation of church and state, marking a turning point toward modern nation. Language diversity followed as the usage of Latin declined, being replaced by national languages in administration and intellectual life, further reflecting Europe’s evolving political and cultural landscape.

From these conflicts emerged the vision of unity and shared identity beyond religious or territorial divisions. The ambassador highlighted how these ideas would build a European Union. Furthermore, the ambassador discussed how the EU represents a hybrid model: a combination of supranational authority (e.g., the European Central Bank and the European Court of Justice) and confederated interdependence, promoting shared sovereignty to prevent conflict. The ambassador highlighted Europe’s achievements in economic integration, and reduced inequality, while expressing ongoing challenges in defence, and political cohesion. He concluded by highlighting Europe’s role as a model for multilateralism, emphasising the continent’s historical lessons in cooperation and shared governance as essential for a peaceful global order in the 21st century.

Questions asked by the Scholars:

Q: Can institutions like the WTO accommodate China, or do they need to change?

A: Institutions such as the WTO don’t need to be eliminated, but internal reforms are necessary. China should be given space to participate meaningfully, but reforms should also address situations where permanent members violate rules, potentially restricting their voting power. This approach allows continuity while adapting to new global realities.

Q: How does China perceive Europe geopolitically?

A: China views the EU as an “unfinished building,” recognising its potential for alignment but also noting differences, especially regarding Russia. Europe’s growing focus on economic security contrasts with China’s long-standing strategic approach. China hopes for cooperation, but the relationship is complex and requires careful balancing with U.S. influence.

Q: What are the main challenges in EU-China relations?

A: Key challenges include imbalances in diplomacy, strategic coordination with the U.S., and Europe’s need to strengthen industrial and trade policies. Careful planning is essential for building sustainable cooperation and avoiding division within the global south.