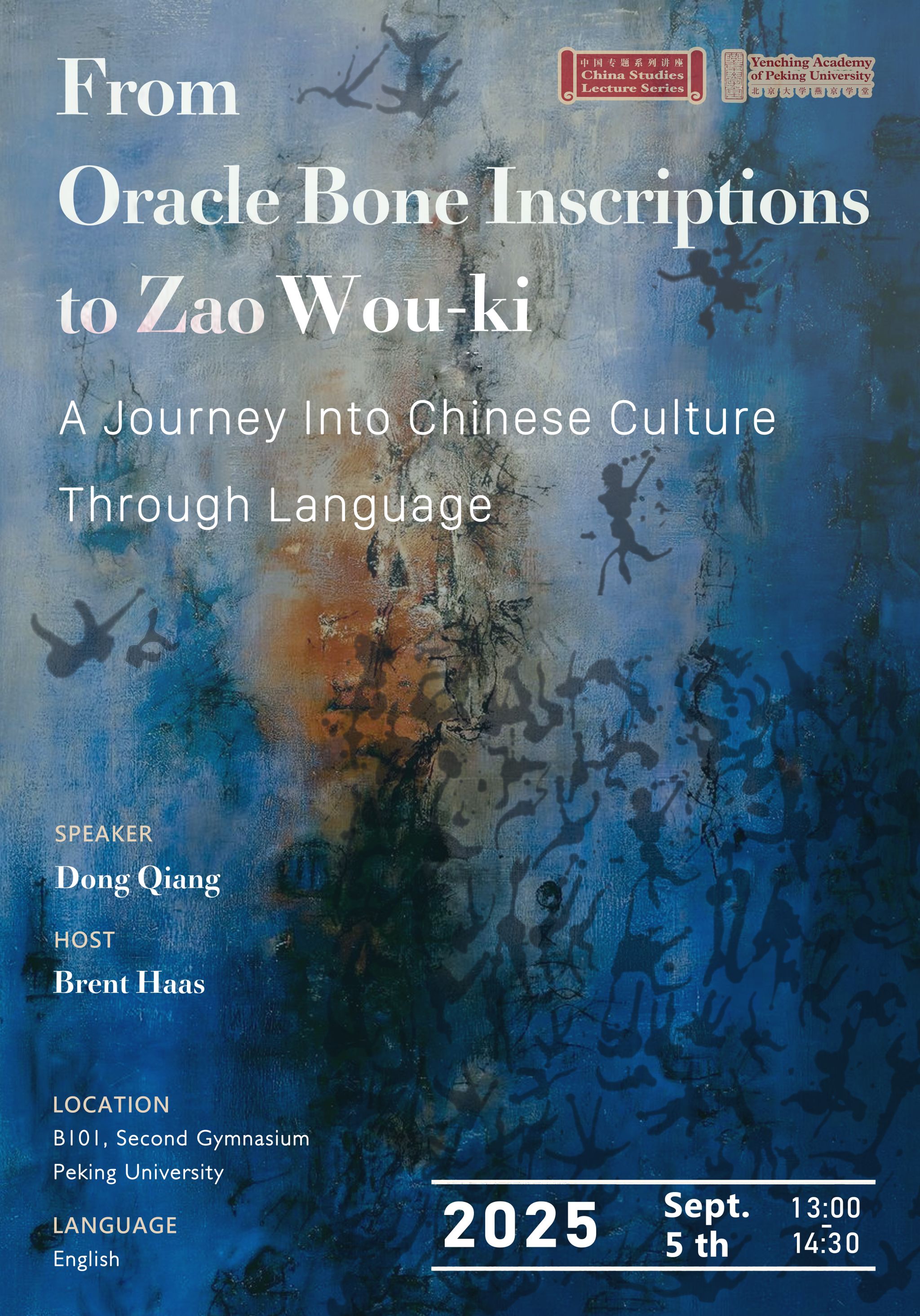

On September 5, Boya Distinguished Professor of the PKU School of Foreign Studies and Yenching Academy Dean Dong Qiang delivered a lecture titled “From Oracle Bone Inscriptions to Zao Wou-Ki: A Journey Into Chinese Culture Through Language” in English at the Yenching Academy. “Custom-made” by Prof Dong for the Cohort 2025, this was the inaugural lecture in the Topics in China Studies Lecture Series for the 2025‒26 academic year, hosted by YCA Associate Dean Brent Haas.

Interview Notes

In an interview before the lecture, Prof Dong Qiang pointed out that the biggest “pity” for a translator is not being unable to make a word-for-word translation of texts but failing to deliver major cultural achievements in translation. The professor highlighted that a translator’s first and foremost mission is to see and deliver the essence of cultures he is familiar with, as every nation has its own distinctive culture and thought. On the other hand, Prof Dong stressed that a text finds no formally perfect equivalent in another language, because languages are fundamentally different; for instance, a sonnet hardly sees a syllable-for-syllable Chinese translation, because it is written in a multisyllabic Western language, while Chinese is the only monosyllabic language in the world. Nonetheless, Prof Dong assured that translation means to describe or explain the essence of a thing to people from different cultures. He took the famous Chinese dish “Mayi shangshu” for example. The dish name literally means “ants [are] climbing a tree” yet the translation sounds meaningless to an English customer. Dong pointed that language is both substantive and arbitrary; that is, a concept can be explained in various ways when different languages are used. Therefore, “Mayi shangshu” can be described as “stir-fried vermicelli with minced pork,” to clarify its ingredients and cooking method. Prof Dong believed that translation must be reader-oriented. If a translation cannot be accepted or understood by the target-language speakers, it is meaningless to overly focus on details and fidelity to the original text.

Prof Dong also discussed the complexity of cultural identity by citing Zao Wou-Ki’s art. Zao was known for rejecting “chinoiserie” and retuning to “the Chinese spirit.” Which may have seemed to contradict himself. But one must understand the issue in the historical context. Zao was against “chinoiserie,” a fashion trend emerging in 18th-century France and obsessed with the exoticness in Chinese decorations. Zao rejected “chinoiserie” because it was a superfluous stereotype of China. Prof Dong said that Zao Wou-Ki wanted to materialise China’s rich history, culture, and philosophy in his art. He saw the essence of the Chinese culture in both the patina on ancient bronzes and the majestic style of the Tang and Song painting. So, Zao dedicated himself to expressing “true China” in his abstract art, in contrast to market-catering “chinoiserie.”

Dean Dong noted that distinctiveness and individuality of a culture must be cherished and preserved, especially as the world seems to be overshadowed by global convergence displayed in lifestyle, technology, and education. Against this background, Prof Dong highlighted that YCA’s cross-cultural program offers a platform where Chinese and international students alike grasp the essence of the Chinese culture as being both distinctive and universal. He emphasised that true-sense education enables students to see the unique values and universal meanings of a culture. He hoped that our YCA Scholars forge a deeper understanding of China’s position and its contributions to the world from cross-cultural perspectives. Prof Dong called young scholars to leverage their cross-cultural competence to build a harmonious world of diverse cultures.

Review of the Lecture

The lecture proceeded in three parts: the characteristics of the Chinese language, its history and culture, and its infinite potential.

Prof Dong first introduced the key features of the Chinese language by first citing Saussure’s modern language theory: Language is a system of signs, and each sign is composed of two parts, a signifier (word or sound-pattern) and a signified (concept). The Chinese language is a dual “signifier” system; that is, a Chinese character is a phonetic-written form. It is difficult to learn for foreign students who are accustomed to a phonetic alphabet. Chinese is a monosyllabic language that uses four primary tones to distinguish word meanings, concise in form yet complex in rhythm. Prof Dong cited “Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den”, a tongue twister crafted by the Chinese linguist Zhao Yuanren (1892‒1982), to demonstrate that the graphic form of Chinese characters is the fundamental criterion for the word meaning, hence why there is particular emphasis on writing in Chinese.

For millennia, the Chinese language has retained a stable core of being meaning based, and undergone a radical evolution of its vocabulary and grammar, leading to enormous differences between the ancient Chinese and the modern Chinese. Chinese is a dynamic language known for its grammatical flexibility, allowing for shifting roles between functional and lexical words.

The Chinese vocabulary encompasses enormous borrowed words from other languages. Prof Dong gave specific examples of Chinese loanwords from English, Japanese, Arabic, French, and Russian, and explained the “domestication” principle in Chinese word-borrowing from a translator’s perspective.

Dean Dong reviewed the evolution of Chinese language from historical and cultural perspectives. He recommended two linguistic classicals on the Chinese language. One is Xu Shen’s Shuowen jiezi (Explaining Simple and Analysing Compound Characters), and the other Liu Xie’s Wenxin diaolong (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons). Shuowen jiezi is not only China’s first lexicographical monograph on the shape and formation of Chinese characters, but one of the first dictionaries in the world. In Shuowen jiezi, the author and lexicographer Xu Shen defined “liushu”, that is, the six categories of Chinese characters—pictographs, self-explanatory characters, associative compounds, phono-semantic compounds, mutually explanatory characters, and phonetic loan characters. “Liushu” provides the fundamental framework for understanding Chinese language and seeing how the Chinese way of thinking and rhetorical expression has been shaped by the language. In Wenxin diaolong, Liu Xie explored the aesthetic concerns and principles of writing and literature. This work marks a new-high of the Chinese language: The Chinese language and literature is explored as a reflection of nature and cosmic, as an interplay between human and the world, and as a communication between “mind” and “external things” (“Spiritual Thought or Imagination” in Wenxin diaolong).

The Jingyuan courtyards are immersed in Chinese wisteria in spring; this “tapestry woven from purples” is not only one of the most amazing sceneries on the PKU campus, but a most cherished memory for our Yenching Scholars. For this reason, Prof Dong selected Chinese literary works concerning Chinese wisteria for a nuanced comparison between ancient and modern Chinese language. One is a traditional poem Chinese Wisteria, written by the Ming poet Wang Shizhen in the form of eight lines with seven characters a line. The other is a modern prose A Waterfall of Chinese Wisteria, written by the modern Chinese writer Zong Pu. Through the comparison, the professor highlighted the differences in way of expression between ancient and modern Chinese language, and revealed the constant quintessence of Chinese literature as being the interplay between the inner and outer worlds. Prof Dong also analysed the differences between traditional and simplified Chinese characters, highlighting the necessity of and principles of the simplification process.

Dean Dong examined the potential of the Chinese language, drawing on his expertise in the comparative study of Chinese and Western cultures and promoting Chinese culture abroad. He stressed on the significance of the Chinese language, from the oracle bones discovered at the end of the 19th century to how artists such as Zao Wou-Ki drew inspiration from the Chinese language. The professor placed the discovery of oracle bones on a par with Jean François Champollion’s decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs 100 years earlier. Prof Dong considered this discovery as one of the most fascinating moments in human civilisations. When the bones bearing China’s earliest writing were discovered at the end of the 19th century, the ancient Chinese nation was also being exposed to Western civilisation, embarking on the journey toward a modern society. Wang Guowei, one of the Four Masters of Oracle Bones epitomised the era of cultural confluence and clash.

Many foreign scholars, literary figures, and artists in various fields, from modern psychoanalysis to cross-cultural poetry, have forged a unique and profound connection to Chinese characters and culture, in their research and creative work. Jacques Lacan, a French intellectual and important figure in the history of psychoanalysis formulated, “The unconscious is structured like a language.” Language is not only an instrument of communication, but more of the core element of subjectivity and the unconscious. To elucidate the concept, Dean Dong took the works of Paul Claudel and Victor Segalen as example. Paul Claudel served as a French diplomat in China and Japan where he was enormously inspired by the aesthetic of the East. To this end, as a poet, Claudel published Cent Phrases pour Éventails (A Hundred Phrases for Fans), a collection of poems Claudel composed under great influence of the art of Chinese characters. Victor Segalen drew inspirations from the ancient Chinese stele inscriptions and published the collection of poems Stèles (Stelae). He jeopardised French poems with inscriptions from ancient Chinese stone tablets, integrating modernist poetry with Chinese forms and idea.

A t the end of his lecture, Dean Dong elaborated on the influence of oracle bones and bronze inscriptions on modern art, by examining the Chinese-French artist Zao Wou-Ki’s art. By drawing inspirations from oracle bones, Zao shifted his art style from being under influence of Paul Klee to representing the ethos of Tang and Song dynasties, and became one of the most prominent Chinese modern artists of the 20th century. Throughout his art career, Zao was encouraged by his friend Henri Michaux. A poet and painter himself, Michaux had a strong love for and was heavily influenced by Chinese calligraphy, creating a distinctive art style thereof. Under Michaux’s influence, Chinese calligraphy was borrowed by other art forms, such as modern dance, as a source of inspiration.

Dean Dong summarised that the Chinese language has, since the day of its birth, echoed the origin of the world. The Chinese language and culture are never restrictive; instead, it has enormous capacity of self-renewal and evolution. The Chinese culture invites reflections on the world, which is, in essence, in constant flux, as described in Ching. Therefore, the Chinese language has infinite potentials generated by openness and focus on cosmos.

In the Q&A Session, Dean Dong and our Scholars looked at the issues such as the tension between modernisation process of language (language simplification in particular) and language tradition, as well similar emphasis on language in the Chinese and French cultures. Dean Dong noted that the Académie Française, as the official authority on the French dictionaries tries to find a balance between keeping the language purity and adopting new words. French President Macron emphasises the importance of language. All these showcase France’s respect for and preservation of its language. China has had similar efforts for the Chinese language. Language simplification is a common challenge for all languages. The problem exacerbates in the digital age, as people increasingly tend to use emoji, undermining the richness and subtlety of language. Every culture has to adapt its language to modern needs while preserving the language tradition; it is a common challenge. Social development requires easier languages for efficient communication; but in the meantime, we need to preserve the richness and historical traits of language. Language is more than an instrument for communication; it is culturally and emotionally significant. The preservation of language traditions and respect for the “life” of language are critical for cultural diversity and international communication.

Dean Dong hopes that the Chinese language will one day become a global language, and in an increasingly AI-dependent age, the Chinese language can become a link between the inner and the outer, helping people remain true to their own heart and mind. Readily willing to contribute one’s own efforts, Prof Dong invited the Scholars to join him in the development of the Chinese language.