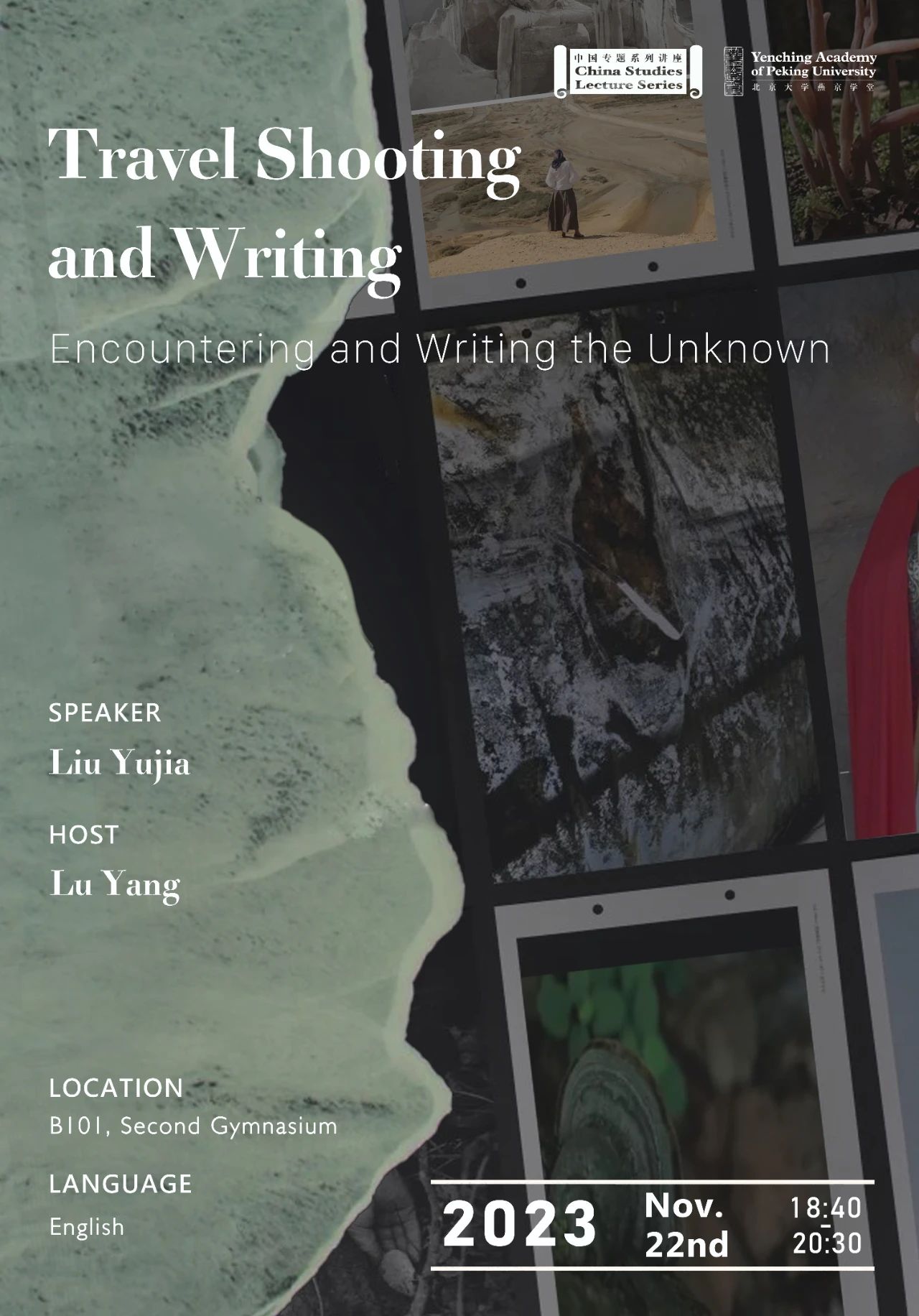

On Wednesday, November 22, 2023, Yenching Scholars embarked on an immersive journey into a world of uncharted territories, captured through the lens and narrated through the words of Chinese artist Liu Yujia in a lecture titled “Travel Shooting and Writing: Encountering and Writing the Unknown.” Through her fieldwork and photography in Xinjiang and Northeast China, the speaker invites the students to step into fresh and fascinating perspectives of the relationships between humans and the natural world, as well as the cultures and livelihoods of rural Chinese people.

Professor Lu Yang, Director of Graduate Studies at Yenching Academy, hosted this Topics in China Studies Lecture Series class. He shared his experience of first encountering Liu Yujia’s exhibition, “A Darkness Shimmering in the Light,” curated by art historian Mia Yu and held at Tang Contemporary Art Beijing 1st Space. This occurred during the summer of 2023 when he received an invitation from a group of Yenching Scholars from the 2022 cohort, led by Raquel de Sá from Brazil.

Adopting a travel shooting and documentary-led approach, where unscripted documentary footage is seamlessly woven into fictional narratives, Liu Yujia shared five stories and several short video clips from her travels and writing process. Her objective has been to explore whether a new empirical perspective of perceiving space and location can be distilled from the scattered, seemingly unconnected vignettes of different locales. She remarked, “To some extent, those encounters are gifts that my team and I have received in the vast uncertainty of the field. They are precious experiences I cannot fabricate only with my imagination; there must be a combination of embodied experience and imagination.”

The first story, “The Relationship Between Tamarix Cone, Historical Relics, and Environmental Changes,” unfolds in the fall of 2019. Liu Yujia embarked on a filming expedition, capturing the untamed beauty of the desert landscapes in Lop Nor and the downstream area of the Tarim River in Xinjiang. Here, she discerned a romantic and poetic connection between the process of sand dune formation and the cyclical vitality and withering of red willows. She explained that these natural elements, with their intricate patterns and life cycles, serve as silent narrators, holding within them a wealth of information that unveils the environmental evolution of Xinjiang.

The guest lecturer also explained another remarkable feature of the landform: it is like a medium or a container of time that stores a wealth of information from distant pasts, and an architectural tomb that houses many antique Buddhist ruins and cultural relics on the ancient Silk Road. She described the discovery of the world’s smallest Buddhist temple – a small structure measuring only four-square meters, hidden within a vast area of Tamarix cones in the Damagou excavation site in Khotan, Xinjiang.

The second story, titled “Illiteracy and Fake Cultural Relics in the Beginning of the Twentieth Century in Xinjiang,” is set in the context of the British and Russian struggle for influence over Central Asia. Liu Yujia recounted her interest in the Bower Manuscript, a collection of seven fragmentary Buddhist Sanskrit treaties, and the life of a young illiterate Uyghur man, Islam Akhun, who produced and sold forged manuscripts as ancient Silk Road texts in the early twentieth century.

Furthermore, Liu Yujia narrated her encounter with a shaman from Inner Mongolia in 2022. The shaman provided his services through live-streamed WeChat videos, “treating” individuals who sought his services. His technique involved chanting incantations and other mantras, directing healing energy towards ailing viewers of his videos in exchange for a fee. Artist Liu explained that, in this instance, the shaman’s body no longer represents the medium; instead, cellphone screens had become a new conduit for practising spirit-summoning rituals and facilitating the exchange of healing energy.

Continuing her discourse on spiritualists, Liu Yujia’s next story led her to Changbai Mountain, where she encountered a Korean witch doctor named Li Shunji. In her account, Liu detailed her conversation with the witch doctor, who asserted possessing special abilities to communicate with animals and plants, honed through a seventeen-year training in the mountains. Also, the guest lecturer described the witch doctor’s spiritual practice of “healing” her Korean patients by chanting mantras while watching Korean TV shows, and a series of setbacks she and her team experienced after vexing the shaman. In this vein, Artist Liu pointed out, “When we are situated in the vast uncertainty of the unknown, we automatically activate our ability to weave mystical and spiritual stories. These series of incidents made us associate the causal relationship in response to something unknown.”

The final narrative, titled “The New Life of Unemployed Couples on the Wild Island,” chronicles the experiences of a couple, Shi Deguo and Cui Jinxiu. The story unfolds after an unfortunate turn of events when they were impacted by waves of layoffs in Northeast China in 1998. Subsequently, the couple made the unconventional choice to live on an island, and the account delved into the challenges and transformations that marked their new life around the bend of the Songhua River. Artist Liu remarked, “In the last part of my film, I portrayed their lives on this small island in a more abstract manner; I didn’t depict their lives in a very realistic and specific way. I wanted to convey warm and hopeful emotions like reminiscing past times or memories because their love story was for big picture films or epic novels.”

Q&A

Q: What is the philosophy behind the production of the series of documentaries, especially considering this style of contemporary art challenges the boundaries between reality and imagination?

A: My intention transcends presenting reality. As a contemporary artist, I believe my job is to present an imaginary world; I could say that I reflect the world through my art. The fictional aspects and the reality are pretty distinct concerning my practice in the different localities I have traversed and documented. Xinjiang offers a more interesting outlook of the fictional layers of reality because many realities are at play and presented by way of fiction. This, however, differs from the more reality-based clips I filmed in Northeastern China. Besides, I have no training in anthropology, but I have read several pieces of literature to gain a deeper understanding of the field and how anthropologists think about exploring unknown environments. This venture has enabled me to realize the necessity of finding a connection between the (fictional) spirit world and myself.

Q: How has the concept of the “outsider gaze” impacted your encounter with the subjects and the production process of the documentaries, which focuses on exploring unfamiliar communities and understanding the unknown?

A: My filming process is usually very long. I always start filming from a landscape point of view as it gives ample room to encounter many subjects and characters. Nonetheless, as a Han Chinese artist working in several minority communities, ethnic issues almost always arise owing to cultural differences. My approach has always been to talk to the people about my intentions, keep a safe distance from their private lives, bear gifts, and show respect for the local values, customs, and traditions. Also, I always show the people the clips after I finish producing them. This effort allows me to listen to their feedback.