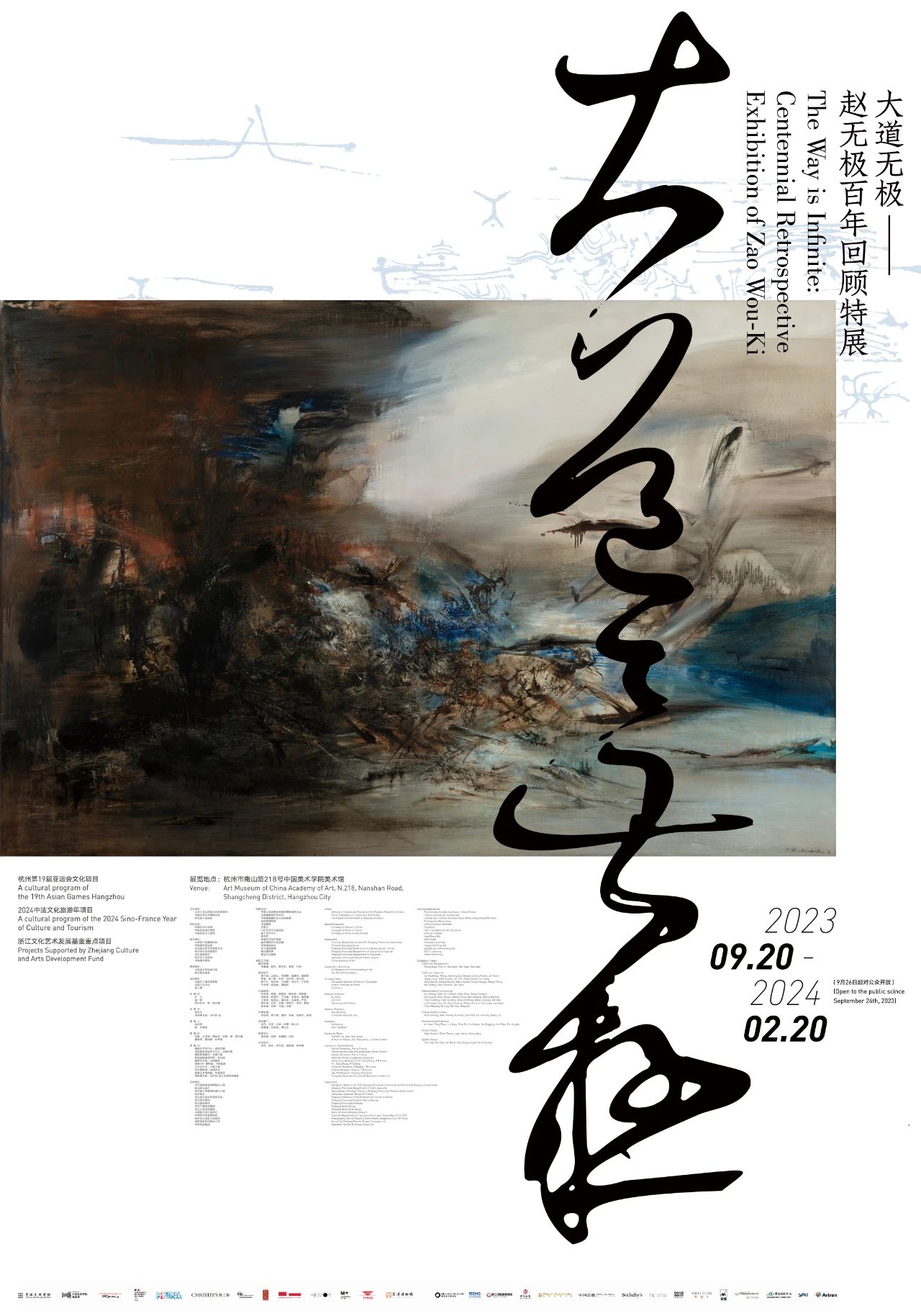

by Dong Qiang

On September 19, 2023, the grand opening of the "Da Dao Wuji - Zao Wou-Ki's Centennial Review Special Exhibition" was held at the Art Museum of the China Academy of Fine Arts. This special exhibition featured a forum on "The Infinite Avenue - Zao Wou-Ki's Art World”. On September 20th, Prof. Dong Qiang, Dean of Yenching Academy of Peking University, delivered a keynote speech titled "Journeying and Looking Back - Following Zao Wou-Ki into His Abstract World" at the forum. The English version of the original speech is as follows:

The “paths” through which we can approach an abstract painting are limited, making it challenging to provide interpretations beyond visual appreciation. This is particularly true when considering artists like Zao Wou-Ki, who firmly believed that his paintings conveyed a clear expression and required no verbal narration. Meanwhile, it is noteworthy that Zao consistently sought the company of language. His close-knit companionship with French poets and critics, and the almost regular “dialogues” he engaged in with them (not only with Henri Michaux), reveal that language, at least poetic language, serves as the “other half” of his artistic creations, echoing the “unspoken messages” within his artworks.

The greatest characteristic of traditional Chinese painting is the “framing together” of poetry and painting. In Zao’s works, however, the two elements are not “framed” together, instead, they “coexist”, inhabiting the same realm, or pointing in the same direction. It is precisely this consistent “dialogue”, or implicit dialogue, that allows us to catch a glimpse of a certain “path” into Zao’s abstract world: if poetry acts as the mirror for his paintings, then his paintings are also the mirror of a certain kind of poetry.

Zao’s artistic creations, even in their seemingly casual brushstrokes, possess a remarkable clarity; his written narratives, despite occasionally lapsing into silence, exhibit a rare lucidity. Therefore, his Autobiography of Zao Wou-Ki (赵无极自传, referred to as Autobiography in the following text for short)1, co-authored with his wife Françoise Marquet, published by Wenhui Press in 2002 and translated by Xing Xiaozhou, becomes an ideal pathway to enter and even traverse Zao’s artistic world. We need to exercise caution and skepticism with eloquent and exaggerated individuals but approach every word of a more reflective and taciturn person with utmost seriousness. Otherwise, human languages will lose their significance, and we will easily descend into true nihilism.

Autobiography was completed in 1988, the 40th anniversary of Zao Wou-Ki’s arrival in France. By then, he has gained worldwide recognition as one of the very few Chinese artists who are truly international, with artworks reaching a pinnacle of excellence in both quantity and quality. The writing of his biography, at that time, is a highly relevant practice that provides a comprehensive examination of his lifelong creative journey. Observant readers may notice that one of the motivations for his writing was his trip to Hangzhou with his wife in 1985. Unlike his previous returns to China, which often involved family matters, accompanied by bitterness and pain of the artist, the 1985 journey is a truly artistic return. The disappointment Zao experienced on this trip became a recurring theme in Autobiography, akin to a “musical motif”, as it fully reflected Zao’s artistic philosophies: a deep abhorrence for “socialist realism”, a strong distaste for blindly following the Western oil painting traditions without a thorough understanding, and an intense lamentation over the lack of knowledge on how to inherit the essence of China’s great artistic traditions.

At the turn of the century, Zao wrote a new preface for his autobiography, expressing his rejoice at finally being truly understood by China and his heightened expectations looking forward. At that time, he had forged a strong friendship with Ma Chengyuan, who served as the Director of the Shanghai Museum, through their shared appreciation for bronze artifacts. The collaborative efforts from both China and France, facilitated by Director Ma and former French president Jacques Chirac, played a pivotal role in bringing Zao’s art into the limelight in China, attracting tremendous attention2. “I felt like I’ve finally emerged from loneliness and become a part of the larger community. No longer constrained as an outsider, I had, at last, found my rightful place.” (Page 2, Autobiography. All subsequent quotes are from Autobiography unless otherwise noted) Zao’s autobiography enables us to delve into his departure from and continuation of China’s artistic traditions, comprehend the transformations in his artworks, and, by following his artistic trajectory, try to understand how a great artist can provide invaluable insights for the contemporary and future art world.

Zao Wou-Ki particularly emphasized that among his many peers, he was “the only one who went to France” (p. 20). He reflected with poignancy, “Who can understand the time I spent to examine and appreciate Cézanne and Matisse, only to return to Tang and Song paintings, which I consider the most beautiful in our own tradition?”(p. 32) The reason for such emphasis is that during that time, many regarded him as an abstract painter who fully embraced Western modernism. Both admirers and critics tended to perceive him as disconnected from China’s traditions. Admirers celebrated his integration into the global art scene as an avant-garde figure, while critics denounced him as a rootless wanderer who had abandoned his traditions. In this context, Autobiography provides the best response to these voices.

Indeed, very few Chinese artists have exhibited the spontaneous and unequivocal determination displayed by Zao Wou-Ki to distance themselves from China’s educational environment and wholeheartedly embrace the burgeoning waves of Western modernist thoughts from the very beginning. “How did you manage to, shortly after you arrived in Paris, befriend those who are now eagerly sought after by museums and publishers, and those who have become great writers and renowned physicians? Paris is huge, and they don’t stay in one room...”(p. 36) This was a question his wife often posed to him. Zao’s response was that he, too, had no answer. The greatness of contemporary France lies in its being a crossroad, a melting pot. It is France, but it is also more than that. There exists a narrow France, but also a broader France that embodies modernity and openness. The France in which Zao resided never demanded people to fall in love with the narrow France; instead, it welcomed artists from around the world as France in its broader sense. This is the fortune of contemporary art, and it is also the fortune of Zao Wou-Ki.

The true value of the book resides in its ability to transcend a mere chronicle of Zao’s life experiences and instead serve as a revelation of his inner journey. Within this personal odyssey, several significant events, intimately tied to his family or profoundly stirring his emotions, have reshaped his artistic expression. However, equally significant are the encounters and interactions with artists from different parts of the world, which have accompanied him throughout his life. Although these encounters may not be classified as major “events”, they have established diverse benchmarks for Zao, enabling him to practice the traditional Chinese philosophy of “mirroring oneself in others”. Amidst the vast diversity of the world, Zao sees his uniqueness with greater clarity.

This uniqueness, in the eyes of others, whether they are French or foreigners from around the world, is inevitably labeled as “Chinese”. This is the daily “struggle” that Zao Wou-Ki faced in France: how to discard the Chinese labels imposed on him, whether intentionally or unintentionally, by others, while still embracing his Chinese identity. In essence, it is a challenge to break free from the confines of “chinoiserie” and still remind people of the greatness of China. Bronze artifacts, oracle bone inscriptions, and the artistic spirits of the Tang and Song dynasties represent Zao Wou-Ki’s China, the China he longed to reconnect with. However, both “chinoiserie” and “socialist realism” represent obstacles between him and his China, not to mention the political ordeals he endured for nearly half a century. As a result, anyone who came close to Zao Wou-Ki, whether they were artists, poets, sinologists, or collectors, perceived the distinct “Chinese spirit” that he embodied. Poet Yves Bonnefoy discussed the artist’s “struggle” and the eventual achievement of “harmony” through integration (Zao Wou-Ki, LA DIFFERENCE/ENRICO NAVARRA Publisher, Paris, 1997, p. 326). Claude Roy, one of his earliest collectors, directly addressed this “integration”. He recognized in Zao Wou-Ki “a classic example of cultural integration between East and West”: “this is a small yet decisive refutation of the dangerous lies that proclaim the complete opposition and fundamental incompatibility of Eastern and Western cultures.” (p. 68)

When we closely examine Zao’s “circle of friends” in Paris and the “Paris School” he belongs to, we can see that they were almost bound to succeed. What they brought and explored was exactly what post-war Paris and even the Western world needed. While art historians almost unanimously claimed that the center of modern art had shifted from Paris to New York, Zao Wou-Ki and his fellow artists stubbornly, tenaciously, and almost silently made their statement: Paris is still a center, or at least one of the two centers. Those who have wandered through the halls of MOMA and marveled at its rich and vast collection of abstract art cannot help but feel a tinge of regret: the collection is so awe-inspiring, but also so American, so New York-centric. The absence of works like those of Zao Wou-Ki leaves a significant void. But it is precisely in this sense of regret that the distinct value of Zao Wou-Ki and the Paris School becomes evident and emphasized.

In fact, if we accept the perhaps overly inclusive notion of the “Paris School”3, Zao Wou-Ki can be placed within the second or even the third Paris School, which could be termed the “New Paris School”. The traditional Paris School witnessed the rise of numerous remarkable artists, many of whom came from Central Europe and Russia, and included a significant number of Jewish artists who rooted themselves in Paris around 1900, thus establishing the city as a genuine center of art. However, the members of the New Paris School come from a much wider range of places, presenting a truly global coverage. While the traditional Paris School did have a few artists from the Far East, like Tsuguharu Fujita, they were rare exceptions. If the artistic pursuits of the traditional Paris School were largely influenced by the local artistic atmosphere in Paris at that time, the members of the New Paris School have embarked on a journey of contemplation of modern art pioneered by artists such as Matisse, Cézanne, and Picasso, drawing from the distinct disparities derived from their own cultures. To illustrate this point, let us consider one example: the Canadian artist Jean-Paul Riopelle, who was a close friend of Zao Wou-Ki, passed away in 2003. Five years later, in 2008, Zao's monumental work “Homage to My Friend Jean-Paul Riopelle” was exhibited in Canada. In the preface, the curator specifically highlighted the differences between the two artists’ abstractions: Zao Wou-Ki’s abstraction is rooted in Eastern aesthetics, characterized by its profound and contemplative nature, while Riopelle’s abstraction is intense, evoking the powerful force of Canadian storms.

The global nature of the New Paris School required the support of new poetics. For artists like Matisse and Picasso, their philosophy finds representation in poets such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendrars, and the surrealists. Similarly, the artists belonging to the New Paris School find support in the works of Paul Claudel, Henri Michaux, and René Char. While the poetic experiments of the former two poets are horizontal, expanding the boundaries of their time, the latter takes a vertical approach, re-examining ancient Greece and Rome. But they all share something in common: emphasis on natural elements, as well as the space (internal and external, infinite). Elemental, intrinsic, and cosmic qualities, as well as spirituality, emerged as new trends. Henri Michaux’s concept of the “inner space” and Paul Klee’s symbolic world opened up fresh possibilities for Zao Wou-Ki, who was grappling with personal suffering, even though his engagement with Paul Klee’s influence led him painfully astray at one point.

Zao’s stance in such an atmosphere is clear-cut: “I want nothing to do with ‘chinoiserie’.” (p.32) This statement is worth pondering. In fact, it does not imply a rupture with China, but rather, a deliberate distancing from the so-called “traditional French painting”, as “chinoiserie” is a typical concept deeply rooted in the traditional aesthetics of France. It was French painters who embraced and popularized “chinoiserie”, making it representative of a certain decorative style. Nevertheless, Zao, throughout his artistic journey, sought to abandon and steer clear of this ornamental quality.

The significance of Paris as a melting pot lies in the fact that artists from all over the world felt the need for a new artistic pursuit. An unprecedented sense of freedom was stimulating and beckoning the artists. The achievements and global recognition of figures like Matisse, Cézanne, and Picasso have placed artists in an unparalleled position; if we look at today’s art scene, we may even say that they remained unmatched throughout history. Instead of “liberty guiding the people”, artists have taken up the banner of freedom and become pioneering trailblazers. It is in such circumstances that Zao, with his Chinese background, offered revolutionary possibilities.

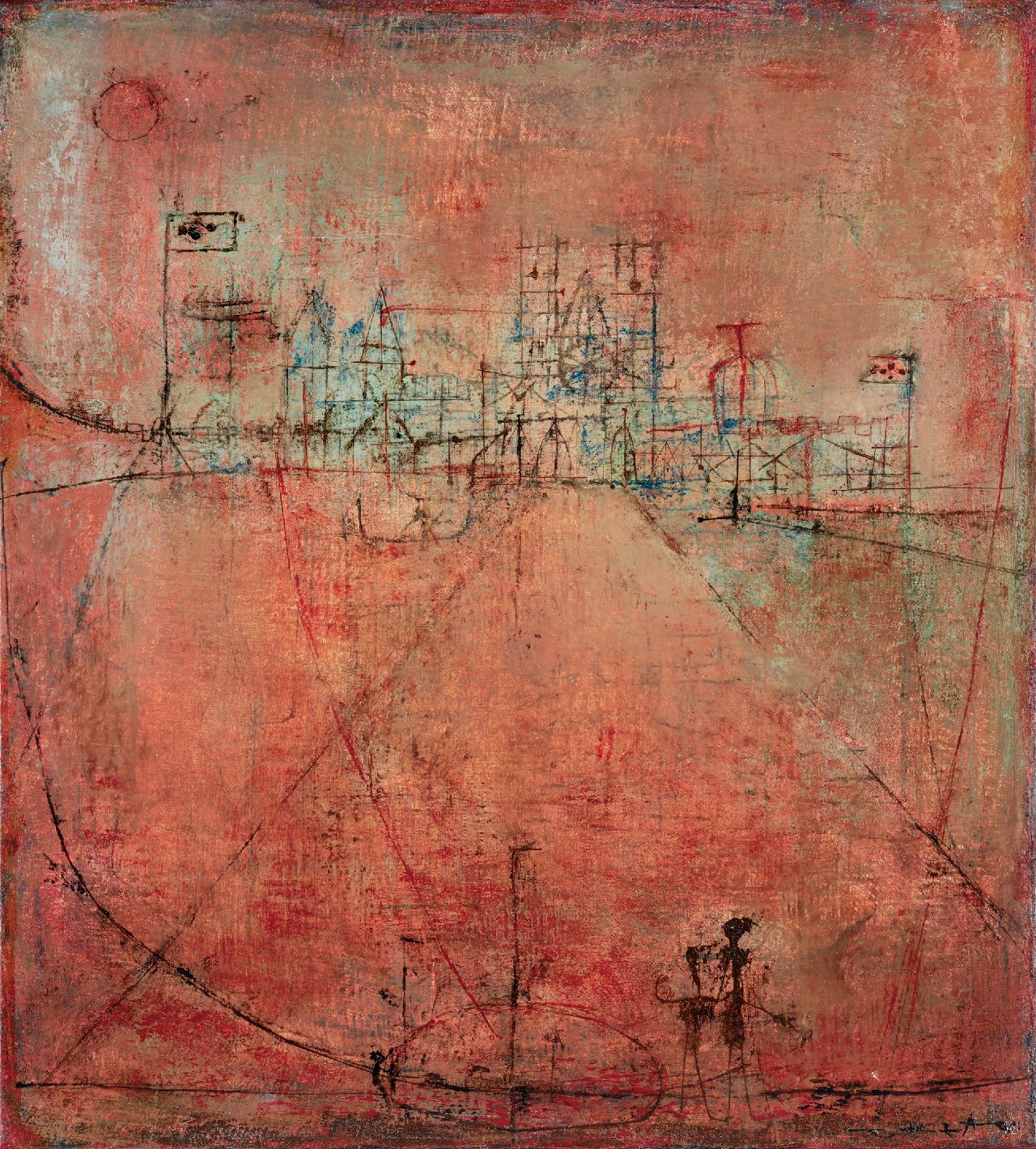

When an artist leaves with us their works, from the initial scribbles to the unfinished punctuation of their final works, what we face is the true passage and accumulation of time. Despite painting being considered an art form centered around space, what we primarily perceive from it is time, or rather, the artist’s evolution within time. François Cheng, who shared a similar life experience with Zao, categorized Zao Wou-Ki’s artistic career into four stages in the preface of Zao Wou-Ki’s exhibition at the Grand Palais galleries in Paris4. From Zao Wou-Ki’s autobiography, we can see that Zao Wou-Ki’s segmentation of his artistic journey is mainly based on significant events in his life and the emotional tremors that followed. This approach aligns with his lifelong friend Henri Michaux, who published the famous “Quelques Renseignements sur Cinquante-Neu années d’Existence (Some Information on Fifty-Nine Years of Existence)”, in which he integrated his literary creations and painting practices into his life experiences. From our perspective, the most significant phase of Zao Wou-Ki’s artistic journey lies in the thrilling years from 1950 to 1957, during which he was initially heavily influenced by Paul Klee, transitioned to ideographic characters in ancient China, and then fully broke away from text and embraced symbols. It began with the famous “Arezzo” in 1950 and culminated in the symbolically meaningful “La Traversée des Apparences (Transcending Appearances)” in 1956. It can be said that starting from 1956, textual symbols have transformed into rhythms and vibrations, while lines have become elements, fundamental particles in the cosmic space, laying the foundation for the later magnificent and vast realm of freedom.

For Zao Wou-Ki, his admiration for Paul Klee is intertwined with his reflection on and connection to China. He believed that Paul Klee must have possessed a fundamental understanding of Chinese painting to create such works. “His (Klee’s) understanding of and admiration for Chinese painting is evident. From the small symbols depicted in multiple spaces, an astonishing world emerged before me.” (p. 55) This might be the first time that Western painting hints to Zao that within his own civilization, there exists something vivid, lively, and modern waiting to be explored. “Western paintings—with the one in front of me (Klee’s work) being the purest example—borrow from an observational approach that is familiar to me, an approach that once puzzled me.” (p.55) It turned out that the “observational approach” he was too familiar with, and once resisted and wished to keep a distance from, can serve as a source of inspiration for Western painting and give birth to a new world.

We can see that modern exploration had a decisive impact on Zao Wou-Ki, inspiring and prompting him forward. Each carefully chosen homage paid to the great modern French masters represents a significant leap for Zao, known for his meticulous approach to naming his paintings. Whether it was the tribute to Monet or Matisse, each marked a milestone in his artistic journey. On the other hand, his tribute was directed towards literary figures like Qu Yuan and Du Fu, whom he believed embodied the true essence of the Chinese spirit. Immersed in the melting pot of modern France, Zao Wou-Ki constantly looked back (at China) and gazed afar (at the world), looking for “like-minded spirits”. He began to understand that the previous rejection of tradition was a new starting point rather than an absolute conclusion. (“I try to explain that artists should not negate traditions like I once did; it serves as one of the catalysts for a painter’s creative process, rather than an endpoint.” (p. 31))

Michaux became the “beacon” for him as he ventured into uncharted territory. It was this French artist who keenly perceived the new state of Zao after his trip to Italy. “Suddenly, the imagery, with the festive ambiance of Chinese towns and villages, joyfully and comically trembling within the cluster of symbols.” Zao fondly recalled, “It is here that the word ‘symbol’ appeared for the first time.” And “gradually, symbols become shape, and background becomes space.” (p. 57) The significance of background becoming space is eloquently expressed by Bernard Noël, the French poet. I will not elaborate on this as my friend François Michaud has already provided a precise and to-the-point analysis. For me, what is most important is that this process coincided with the period during which the text gave place to natural elements in Zao’s creation. Nature re-entered his paintings in an entirely new way. Pierre Cabanne astutely pointed out, when explaining the prerequisites for the origin of “lyrical abstraction”, that whether it is Matisse or Picasso, particularly the Cubists, their innovative practices were built upon urban experiences5. Even in the case of Cézanne and Van Gogh, the nature depicted in their works was still the nature of continental Europe. There is a constant lack of the vast, magnificent scenery truly representative of nature. In this case, lyrical abstraction is precisely a breakthrough that, although it breaks with the traditional perspective technique, is still confined in limited space. Modern painting is calling for its “new world”. The Chinese space brought by Zao Wou-Ki offered infinite possibilities for breaking free from modern urban space, and the modern painting space that built upon it.

The melting pot of modern Paris also brought Zao another intense experience: colors. Zao Wou-Ki’s greatest contribution to the grand Chinese tradition perhaps lies in his infusion of the power of color from modern painting into the vastness of Chinese traditional painting, granting void a legitimate “existence”. It is, at least, an existence that can be perceived by the modern eyes, turning void into a poetic space for tranquil residence. In the enduring debate between “line” and “color” in the West, Zao intentionally or unintentionally turned towards color, which was the most effective way for him to break free from the shadow of Paul Klee. The lines in his works underwent a process of transformation, evolving from thin, black lines predominantly oriented horizontally and vertically, to traces resembling oracle bone scripts and bronze inscriptions, and then to the fundamental elements of nature; it was almost a process of self-concealment of the lines themselves. Lines gave way to gesture, which symbolizes rhythm and movement, as well as the immense cosmic power. Eventually, larger “voids” started to occupy his paintings. These “voids” often manifested as highly evocative colors, except in traditional Chinese ink paintings, where they appeared as white. This is the true rationale for his homage to Matisse: “The opening suggested in his (Matisse’s) paintings inspired me, giving me a genuine urge to enter. This is the path towards infinite solely through colors.”

As poet Yves Bonnefoy pointed out, these are not pure colors6. This prevented Zao Wou-Ki from engaging in a form-centered abstraction, from becoming a Piet Mondrian, or even a De Staël or Poliakov. This exploration, which does not rely on pure colors, brought depth to abstract space after the artist walked away from perspective. Zao himself said, “There is no longer a boundary between symbol and color, and through the combination of tones, I realized the issue of spatial depth.” (p. 63) Upon reaching this unprecedented space, Zao Wou-Ki entered the much-desired “kingdom of freedom”, where everything surges or emerges. Critic Georges Duby was the first to highlight this surge, stating, “It is a sense of completeness in vibration. It is a surge.” (p. 94) Renowned poet René Char, who was less familiar with Zao compared to Michaux, keenly observed this phenomenon. He depicted the spectacular and enduring surge with poetry reminiscent of ancient Greek, saying, “There exists a magic of the lyre of Orpheus the wanderer, ethereal and magnetic. Elements constituting the painting intertwine and constantly give birth to new meanings, like the rich colors constantly changing on the horizon at sunset.” (p. 84) Zao Wou-Ki himself found great satisfaction in this observation, particularly because it offers a way to reconcile with the concept of “infinity”, often metaphorically associated with the sea by modern Western artists. He remarked, “I have never been particularly interested in the sea... I am not sensitive to the concept of ‘infinity’ frequently mentioned by Western poets. I prefer the tranquility of lakes, with their inherent sense of mystery, creating endless changes of colors.” (p. 9) It is safe to conclude that in this ever-changing surge, Zao reached a certain Rimbaudian eternity. (“She was found. -- What? Eternity. It is the sea / surging towards the sun.”)

Zao Wou-Ki’s artistic journey, in the language favored by modern writers, is a true “adventure”, one that combines life and spirit. In this adventurous process, Zao Wou-Ki’s fundamental concerns include how to integrate his creation with the quintessential and grand spiritual essence of Chinese culture, how to transcend the limitations and artistic preferences of his times, and how to reconnect with the most creative, insightful era and elements of Chinese culture, so as to display the greatest possibilities of free creation in the diverse modernity. It is also such attempts that ultimately established Zao as a unique trailblazer in his world, an iconic figure that cannot be ignored in the global history of modern art.

In his pursuit to bring back the lost time, Marcel Proust produced “In Search of Lost Time”; in his attempts to resume lost space, Cao Xueqin created “Dream of the Red Mansion”. Similar to the two literary masters, Zao’s lifelong pursuit is rich and diverse. However, there remains a consistent quest: is it possible to reclaim the China that has been lost (to him)? To put it in simpler terms: Is China returnable?

When writing Autobiography, Zao Wou-Ki, fully aware of his entrenched connection with the world, could say to himself with certainty that China is a place he can return to.

In fact, the true return of Zao Wou-Ki—something he did not live to witness—took place in the first two decades of the 21st century. He not only emerged as a companion and pioneer in China’s contemporary art scene with his reflection and foresight but also stands as a guiding beacon for the future of Chinese art through his artworks. I believed that this remarkable exhibition at the National Art Museum of China will mark the true return of Mr. Zao Wou-Ki, and will serve as the best remedy for his “disappointing” homecoming in 1985. Reflecting upon Zao Wou-Ki’s artistic odyssey and contemplating the path of future development is undeniably inspiring! A returnable China will be a shared artistic realm, a reference point for both Chinese and global artists alike.