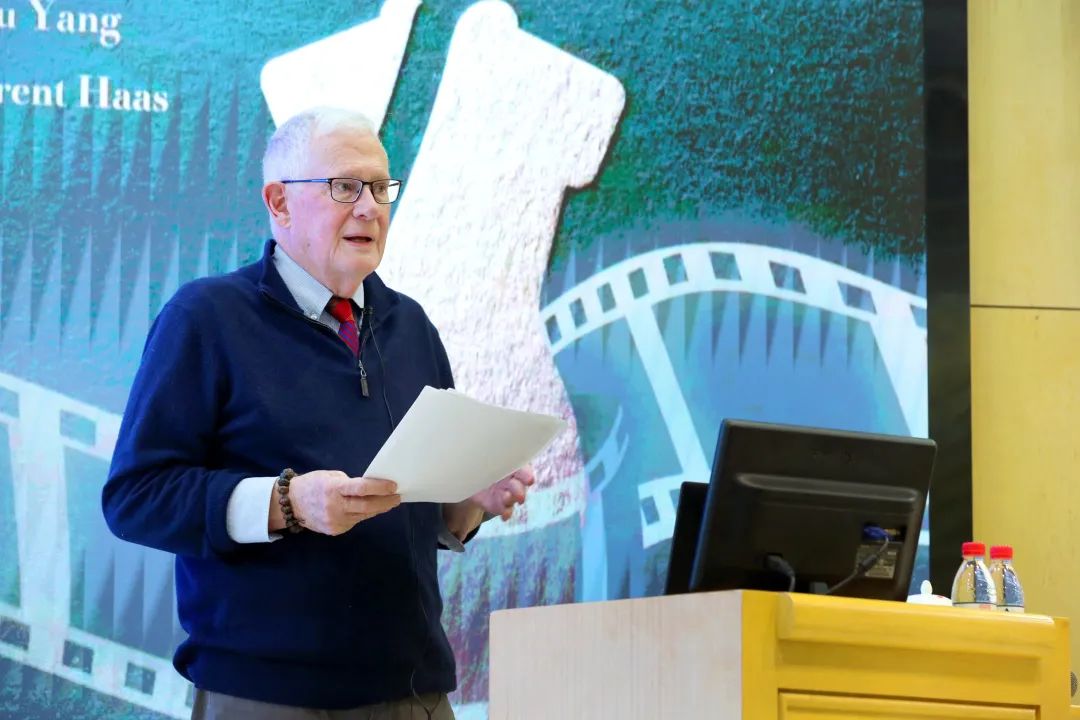

On Wednesday, September 20, 2023, Prof. Paul G. Pickowicz, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History and Chinese Studies, University of California, San Diego, delivered a lecture at Yenching Academy entitled “Women in Chinese Silent Cinema”. This class, which is the first of Yenching Academy’s Topics in China Studies Lecture Series for the 2023/2024 Fall Semester, was hosted by Yenching Academy Associate Dean Dr. Brent Haas, who was also a student of the guest lecturer. The session reviewed the complicated and diverse gender roles in the Shanghai metropolis and other urban settings vis-à-vis the interplay of culture and modernity using clips from rare silent films produced in China in the 1920s to mid-1930s.

Prof. Pickowicz started the lecture by expressing his excitement to return to Yenching Academy, following his previous class with the 5th cohort of Yenching Scholars in 2019. Moving to the lecture’s theme, Prof. Pickowicz highlighted four significant and interrelated points: national allegory, family ties, the struggle for survival, and women. He explained that the concept of national allegory played a substantial role in the evolution of Chinese silent cinema, with the films’ portrayal of prevailing social issues and incitement of debates to find solutions to those problems. He added that many early films focused on families and individuals within them; hence, the families were more or less a stand-in for the nation. Given China’s road to modernization was unfolding in feats and stats and the uncertainty of who the winners and losers would be during the transition, the stakes were high and featured an intense struggle for survival where women played a uniquely dominant role.

Prof. Pickowicz detailed that in the early stages of the Chinese silent films era, most screenplay writers, film-makers and directors were men. He further noted that despite the dominance of men in the movie production process, the presentation of the main women and men characters differed significantly. Hence, he raised two crucial questions that guided the entire class discussions: Why were men film-makers placing women at the centre of these national allegories? And why were the main female characters presented in a sympathetic and positive light, while the main male characters were often viewed as unattractive, liars, and bullies?

To answer these questions, Prof. Pickowicz discussed ten themes linked with sex and violence within the framework of women in Chinese silent cinema using several clips. The first theme he discussed was “curiosity” connected to a film titled “The Big Road (1934)”. The clip shows a group of men bathing in a river and two women passing by, expressing a distinctively modern curiosity about the male body and its implication for their sexuality. Through the clip, the students learned that nudity was not unknown in Chinese silent cinema. Prof. Pickowicz labelled the second video entitled “Oceans of Passion, Heavy Kissing (1928)” with the theme of “fashion”. The film portrays a woman who is confused about the nature of the modern marriage. She is married but has a lover, and this situation leads to a divorce from her husband and the phenomenon of cohabitation with her lover. The third theme, “lies”, is featured in the 1931 film “Peach Bloom Weeps Tears of Blood”. The Scholars watched a scene where a rural woman is the victim of an urban man’s lies about his mother’s approval of their relationship and the events that lead to her death.

The following themes were also discussed in the class: “social class” portrayed in the film “Orphan in the Snow (1929)”; “assault”, “sex work”, and “hatred” depicted in the 1933 movie “Daybreak”; “vamp” illustrated in “A Dream in Pink (1932)”; “discipline” described in “Queen of Sports (1934)”; “take action” displayed in “New Women (1935)”; and “mad woman” featured in the 1933 film “Little Toys”.

To conclude the class, Prof. Pickowicz returned to his two guiding questions concerning the centrality of women and divergences in the portrayal of the main female and male characters. He explained that several reasons accounted for the centrality of women in the silent film era, including commercial considerations, the transformation and expansion of social roles, and the politics of shaming. He argued that the movie producers were driven by the desire to sell tickets and stay in business, noting that “this is consistent with much that we associate with the Hollywood industry – alluring actresses attract large film audiences; it is fine and a bit mysterious to see women on screen in a society dominated by men.” Secondly, he explained that women had more to gain than men in transitioning to modernity across patriarchal societies. Thus, the films portrayed women as experimenting in bold ways to transform and expand their social roles and men as more cautious, insecure, and defensive. Lastly, many male screenwriters were engaged in a politics of shaming, depicted in the contrast between strong women and weak men. “When women are seen confronting all the stresses and strains of the modern age, embarrassed men sitting in the audience are forced to conclude that it is high time for them to stand up, man up, take the lead, and thus, confirm their dominant place in society,” Prof. Pickowicz explained.

Several Yenching Scholars raised questions following the fascinating lecture. One question concerned the classes of people who constituted the main audience(s) for the silent films since the film producers needed people to buy tickets. Prof. Pickowicz explained that the studios and motion picture venues were in the big cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, with high ticket prices for the first run of pictures. Hence, middle- to upper-middle-class audiences were the focus. However, the subsequent second and third runs of the films were usually shown in theatres around the periphery of the big cities, where tickets were sold at lower prices to accommodate lower-middle-class people. Prof. Pickowicz ruled out the possibility of rural peasants seeing the films since remote areas did not have the resources and theatres to show them.

A question peered into the factors that prompted the films to be more progressive, almost feminist, than the state of the society at the time. Prof. Pickowicz noted that the style of the silent film-makers was to show what is happening in society and throw controversial issues without necessarily hitting people over the head with the truth or providing a solution(s) to the problems. Instead, they allowed society to debate the spectrum of views and answers on matters since no one voice exists on any issue. Hence, Prof. Pickowicz expressed: “I like that way of doing social history. Even if you are studying Chinese society today, if you are looking for that one-man answer that explains everything… you’re never going to find it; it is always about a spectrum… So, in that sense, I can regard that as progressive.”

Another question concerned how the addition of synchronous sound impacted the Chinese silent film industry. Prof. Pickowicz noted his discovery after tracking down many famous silent actresses: many of the stars were Southerners and did not speak Putonghua (standard mandarin) clearly. Hence, the emergence of the era of synchronous sounds marked the end of their jobs despite their fantastic talent – body language and facial expressions. Nonetheless, this created opportunities for the rise of a new generation of actors and actresses who spoke clear standard mandarin. Also, the introduction of sound inspired a change in the style of acting in Chinese cinema, breaking from relying solely on facial and bodily expressions to dialogues.