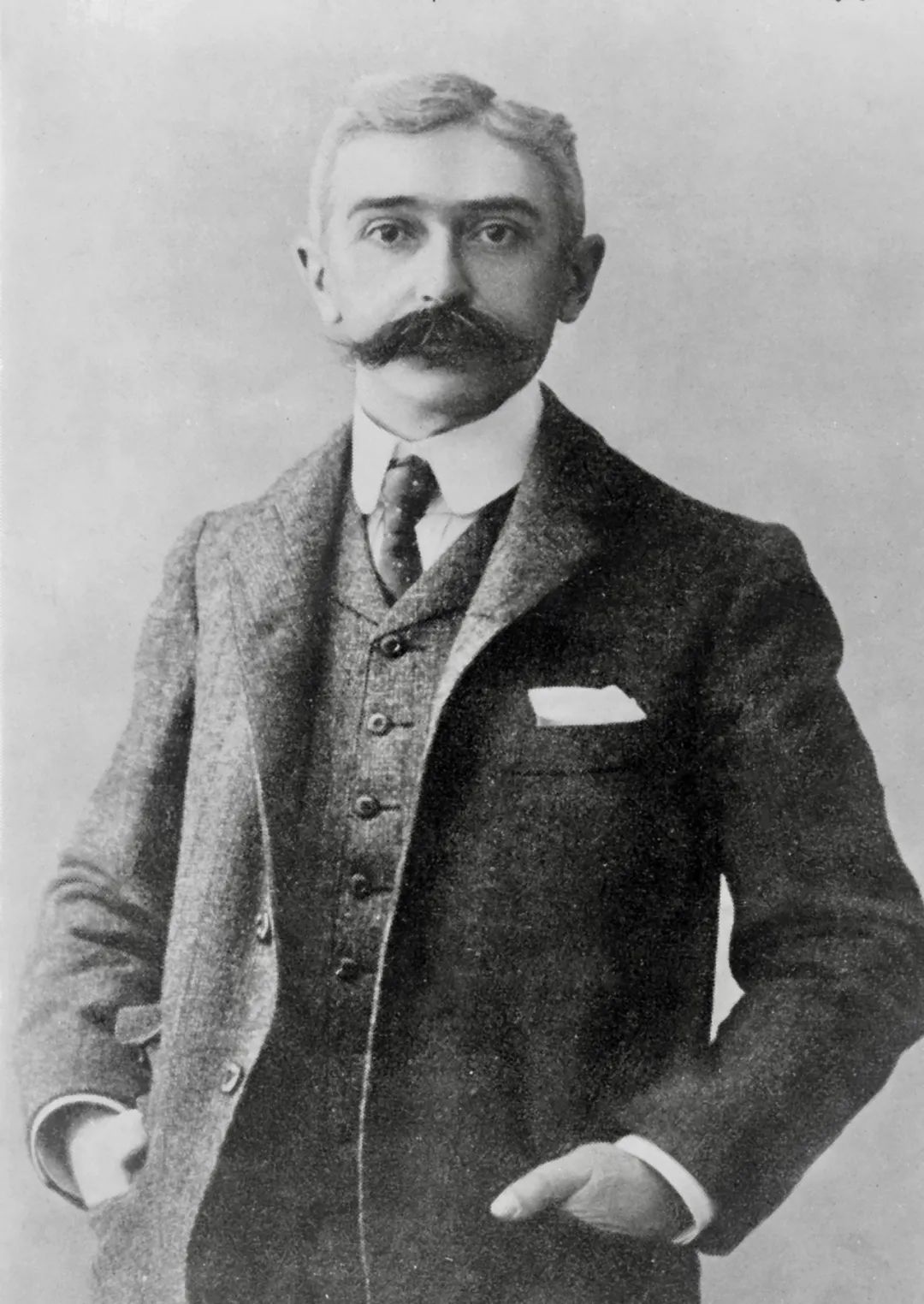

Editor’s note: On March 7, CGTN Français had a video interview with Professor Dong Qiang, Dean of the Yenching Academy of Peking University. Prof. Dong discussed his thoughts on the Olympic Manifesto and the Olympic spirit proposed by Pierre de Coubertin, who is considered the founder of the modern Olympic Movement.

Q: On January 2, 2008, a special issue of the Olympic Manifesto in Chinese, French, and English was published to celebrate the 145th anniversary of Baron de Coubertin. Prof. Dong, you worked on the translation of the Manifesto. Could you share with our audience what the monumental work contains?

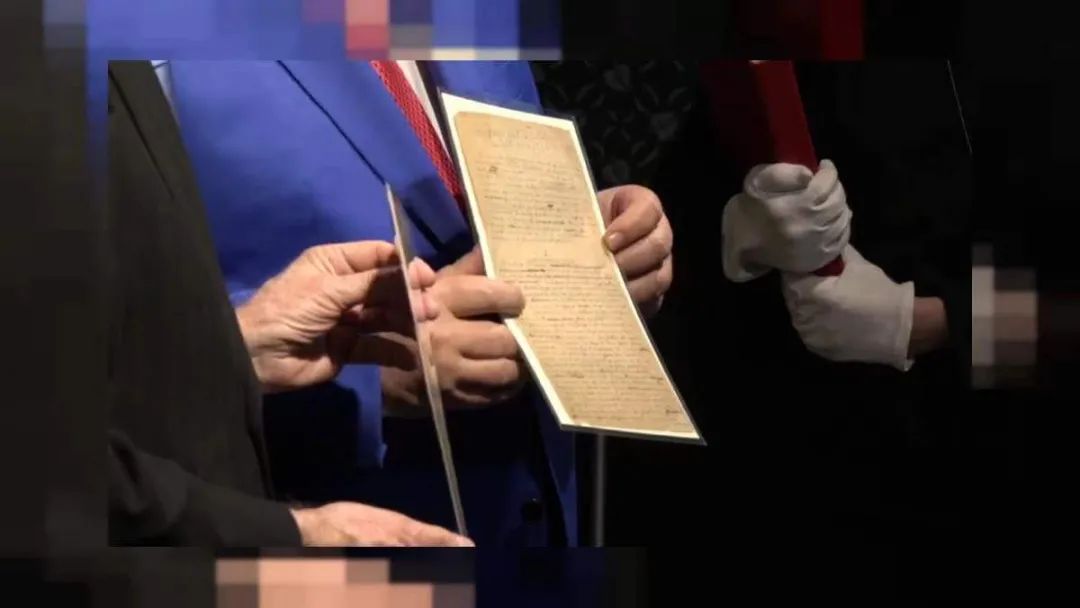

A: Yes. I still feel happy and honored to be a member of the translation team tasked with translating the historic document, an invaluable 14-page manuscript written in 1892. The manuscript was a speech delivered by young Pierre de Coubertin during the fifth-anniversary celebration of the Union of French Societies of Athletic Sports. Coubertin was the Union’s Secretary-General at the time. He analyzed the sports in Sweden, Germany, Britain, the United States, and France. Toward the concluding section of his speech, something miraculous seemed to have dawned on Coubertin. He crossed out what he had initially written, rewriting an inspired passage calling for “the re-establishment of the Olympic Games.” That was at the end of the 19th century. Coubertin was the first to announce the revival of the modern Olympic Games. The manuscript is very precious, but it was long lost before its discovery. I was entrusted with the Chinese version. A grand donation ceremony was held two years ago where the historic manuscript was donated to the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, returning to its Olympic home. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) President Thomas Bach delivered an emotional speech at the ceremony, stressing the document's historical significance and expressing his happiness to see young Coubertin’s manuscript return to the Olympic Museum.

Q: What impresses you most in the Manifesto?

A: The landmark document was later known as the Olympic Manifesto. The then IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch was excited at reading the manuscript and saw its importance because it was the first call for the revival of the Olympic Games in the modern era. The manuscript was thus called the Manifesto. I was inspired by the visionary idea, mainly because the event seemed to be impossible given the conditions at the time. Coubertin investigated the situation in different countries and highlighted various trends in sports. For instance, track and field sports in Germany were for military training, while Sweden’s gymnastics were elderly- and children-friendly. Coubertin, farsighted as he was, admirably pointed out that sports were not for a single nation but for humankind. In addition, Coubertin had a sharp vision that sports would be a popular, international movement, encouraging peace among nations through nonviolent competition. He saw the time was ripe. We can say that Coubertin foresaw what would happen later. With this vision, he established the International Olympic Committee two years later. What happened next is known to all. The first modern Olympic Games were held in Athens.

Q: What does the Olympic spirit mean to you?

A: We are talking about excellence – going higher, stronger, etc. But when you read Coubertin’s Manifesto, you see his primary idea about the Olympic Games was peace and building a better world through sports. For Coubertin, sports and track and field sports, in particular, could help people live better lives in modern society. People could better know one another, and nations could get closer through sports. That is what Coubertin meant by “popular” and “international.” Sports are for the common good and unite ethnic groups, nations, and humans.

Q: How would you describe the relationship between the Olympic spirit and the idea of “a community with a shared future for mankind”?

A: Interestingly, young Coubertin observed differences in sports across different countries in the late 19th century. The sports varied across countries in the north and those in the south. People in a country were good at one sport but not at others. It was generally believed that sports stood in each other’s way. For example, a country particularly good at one event would appear weak if they engaged in another with limited expertise. Coubertin saw the issue differently. He did not think that way. Instead, he called for the full development of all sporting events and common development among nations – for a common goal. Sports are not for a single country’s interests. Instead, sports must be for all races. All nations must have a common goal. That was something like “a shared future.” Of course, it was not called that, but the essence was the same.

Q: “Together” was added to the Olympic motto last year. And Beijing 2022 Winter Games had the official motto “Together for a Shared Future.” What does “Together” mean to us in the post-pandemic era?

A: If we peruse Coubertin’s historic texts, we understand that sports are for the entire humankind. Let us think about it for a moment. I just mentioned geographies, and I believe that is why we have the Summer and Winter Games. We need Olympic and Paralympic Games for all four seasons, for all the people in the world – men and women and the physically disabled, without discrimination. Solidarity is crucial because it means the universality of the Games. The Olympic spirit surpasses differences between nations. We are undergoing lockdowns and border closures in the pandemic. I hope that sports, both the Olympic Games and other sports events, can help people communicate with one another. I hope that we can watch sports contests sitting in the audience and cheering our athletes and teams, and global travels will return to normal in the near future.

Q: In what aspects does traditional Chinese culture agree with the Olympic spirit?

A: A big question. If you look at Chinese history, you would see that physical education was not a priority of the Chinese authorities for quite a long time. The civil service system prevailed in ancient China. The system required capabilities such as calligraphy, poetry, and essay writing from the scholar-officials. But we can also find something parallel to the civil service system from the very beginning. We know Confucius as a great philosopher. If we see him in a modern sense, he attached importance to sports. Confucius was a big and very strong man. Physical education had a place in his educational philosophy. For instance, Confucius highlighted archery skills and saw them as part of “propriety.” Traditionally, a perfect person in ancient China must “be able to wield both the pen and the sword.” Besides, ancient Chinese philosophy believes in the unity and harmony of the body and spirit. The body and the soul are part of the cosmos, and man must respect nature and pay close attention to physical and mental health. When China started its modern chapter in the early 20th century, great educators such as Cai Yuanpei called for the development of physical education in China. Physical education was thought to be indispensable in personal development for men and women. It has been a principle of education in China to cultivate talents equipped with moral grounding and intellectual and physical ability.

Q: Beijing is the first city to host the Summer and Winter Olympic Games. What legacy will the city’s experience leave for China and the world?

A: First of all, we can see Beijing's urban planning and development. I came back to China in the early 2000s. I am always awed at the brilliant urban planning and construction in Beijing. It is remarkable. The two Olympic Games played a great role in this. Beijing took on a new look in 2008 with the Bird’s Nest and Water Cube. We now have many other unique buildings for the Winter Games. The planning and transport in Beijing have kept improving. That is the most direct impression.

Likewise, a city to host the Summer and Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games must be inclusive and open. China is a country of an open mind. Chinese people are always good at learning and learning fast. It is one of our strengths to be good at learning. We knew little about sports. Many sports events were unfamiliar to us. For instance, Winter Games were particularly unfamiliar to the Chinese. Now, the story is different; many Chinese people play winter sports. In this way, we even know better of our large country. We can play so many sports outside the well-known ones in track and field on its vast land. The two Olympic Games held in Beijing, one in summer and the other in winter, are like sparkles. With them, we gain a broader horizon – a more expansive imagination. For our children and students, they will enjoy better sports facilities and better conditions for physical education, in a general sense.